Why in the Ottoman Empire for visiting coffee houses could be executed

There was a period in history when European and Asian rulers imposed a ban on coffee. It is said that in 1633 the Ottoman sultan Murad IV, dressed in simple clothes, wandered the streets of Istanbul and personally chopped off the heads of the violators. Why did the sultan execute? For meetings in coffee houses. He believed that drinking coffee publicly could lead to government unrest.

Ottoman Sultan Murad IV

Ottoman Sultan Murad IV Oddly enough, this sounds, but Murad IV was neither the first nor the last to ban coffee. Perhaps he was the most cruel and consistent in his actions.

Between the beginning of the 16th and the end of the 18th centuries there were many religious figures and public leaders who sought to ban the use of coffee. But few have succeeded. Many of them thought that, despite the fact that coffee had a mild relaxing effect, it was still bitter, unpleasant in taste. Many, including Murad IV, believed that coffee houses could undermine social and behavioral norms, encourage seditious thoughts, speeches, and even be the center for organizing anti-government conspiracies. In today's world, where Starbucks is ubiquitous, it looks wild. But Murad IV had reason to think so and be wary of coffee establishments.

"Coffee Pursuit" began in the 16th century. It was then that the drink spread throughout much of the world. By that time, for many centuries, coffee beans were familiar to the inhabitants of Ethiopia. The first confirmed historical evidence that they knew how to make coffee - ground and brewed - dates back to the 15th century. It happened in Yemen. There, local Sufis used the drink in religious ceremonies. Drinking coffee was of social importance and was used as an opportunity to rally people into a brotherhood, help concentrate during prayer, and achieve spiritual enlightenment. The drink quickly spread throughout the Red Sea region, from there it got to Istanbul at the beginning of the 16th century, then - to Christian Europe.

Servant serves coffee to Yemeni merchants

Servant serves coffee to Yemeni merchantsIn response, representatives of the conservative part of Muslim society put forward several religious reasons for the ban on coffee. The historian Madeleine Zilfi, specializing in the period of the Ottoman Empire, indicates that in Muslim society there will always be a part of believers who will resist any innovations other than the time of the prophet Muhammad. All inappropriate should be discarded. Reactionary trends are not unique to Islam; Christians also asked the pope to ban coffee, as a satanic innovation.

Opponents of the drink said that coffee intoxicates drinkers. And this is forbidden by Muhammad. It is harmful to the human body, frying has made the drink the equivalent of charcoal and this should not be consumed. Others blamed coffee for having attracted people prone to immoral behavior. They gambled there, smoked opium and engaged in prostitution. The third was enough that it is just new, and this is enough to ban.

But religious arguments may not be sufficient and the only reason for the closure of most coffee houses in the Ottoman Empire.

As historians note, the upper strata of society were far from homogeneous in their opposition to coffee. Bostanzade Mehmet Effendi, the most respected priest in the Ottoman world in the 1590s, even wrote a poetic ode to defend coffee.

Most often, rulers opposed coffee for political reasons.

Ottoman coffee house, 1819

Ottoman coffee house, 1819Before coffee houses appeared, Zilfi notes, there were not many establishments in the Ottoman Empire where people could get together and talk about public affairs. It was possible to meet in the mosque, but there is unlikely to have a long and peaceful conversation. Taverns were not for true Muslims, and visitors usually had fun talking to people.

Coffee houses, however, were considered a very suitable place. They were inexpensive and affordable for all walks of life. The way they prepared coffee — slowly brewed in a special coffee pot for 30 minutes, and then served in a bowl filled to the brim so hot that the drink could be drunk only in small sips — had visitors for long gatherings and the opportunity to talk about everything. Coffee houses were a new public space that eliminated class distinctions and set people up for political talk about the country's structure, government policies and the Sultan. The authorities were preoccupied with maintaining social order and stability. They made it clear that they disliked public speaking in coffee houses. Regardless of who says there - a poet, a preacher or an artist

Authors such as the 17th-century Ottoman scholar, Kyatib Celebi, a government official from a wealthy family, wrote about coffee houses as places that "distracted people from their activities." Moreover, "people, from the prince to the pauper, amused themselves by cutting there with knives."

The first official ban on public drinking coffee was introduced in Mecca in 1511 when Khair Beg, a senior official of the pre-Ottoman period, found people drinking coffee outside the mosque. It seemed to him that all this looked very doubtful. The details of this ban are disputed by historians, but one thing is known - the official used religious arguments to prohibit the drink. Later, coffee repressions again occurred in Mecca, several times in Cairo, Istanbul and other areas of the empire.

The first prohibitions were dictated by politics, creed, and often both. But they were single and short. For example, the ban in 1511 in Mecca was lifted a few months later, when the Sultan asked Khair Bega to continue dispersing suspicious meetings on the one hand, and on the other to partially allow people to drink coffee.

The painting "Persian Cafe" Edwin Lord Weeks (1849-1903)

The painting "Persian Cafe" Edwin Lord Weeks (1849-1903)Murad IV had good reason not to like coffee houses. As a child, he witnessed how his brother Osman II was deprived of power and savagely killed by the Janissaries, a military estate that was becoming increasingly independent and discontented. A year later, the Janissaries killed his uncle. After that, they seated the boy Murad IV on the throne. He was only 11 years old. He always lived in horror of the Janissary rebellion and survived several of them at the beginning of his reign. During one of the riots, the Janissaries hung people next to him. One of them was his close friend Musa.

Different types of Janissaries costumes in the Ottoman Empire

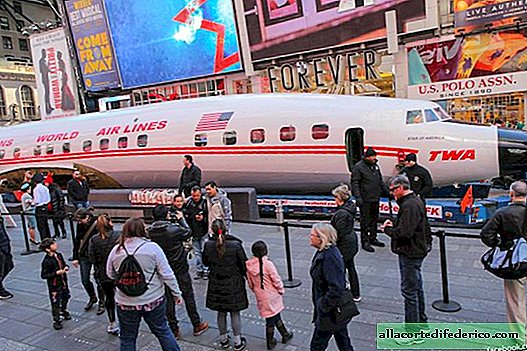

Different types of Janissaries costumes in the Ottoman EmpireThis made Murad IV very strong. The Sultan with difficulty returned power to his hands. This made him become the one whom history will remember as Murad IV the Bloody. He knew that retired warriors often gather in coffee houses and have conversations there. Some institutions specially on their signs placed a sign that the Janissaries are gathering here. A reactionary religious movement was growing in the Ottoman Empire that opposed the Sufis and related secular innovations, including coffee houses. It was in the hands of the Sultan.

He introduced the death penalty for drinking coffee in public places, smoking tobacco and opium. The cruelty of punishment was not dictated by social need, but by the character properties of the sultan himself. Murad IV never banned the sale of coffee in bulk. He did not like coffee houses. The ban concerned only the capital - the place where the rebellion of the Janissaries was most likely. Murad IV himself liked to drink coffee with liquor.

His successors in one form or another continued the course taken by the Sultan. By the 1650s, more than a decade after the death of Murad IV, Celebi wrote that Istanbul was still "as deserted as the heart of the ignorant."

Coffee shop in Istanbul. 1905 photo

Coffee shop in Istanbul. 1905 photoTowards the end of the 18th century, other public venues appeared, and dissent migrated there. Closing coffee houses was no longer ineffective in opposing dissent. The bans stopped, but the rulers still sent spies to them in an old memory to eavesdrop on anti-government conversations.